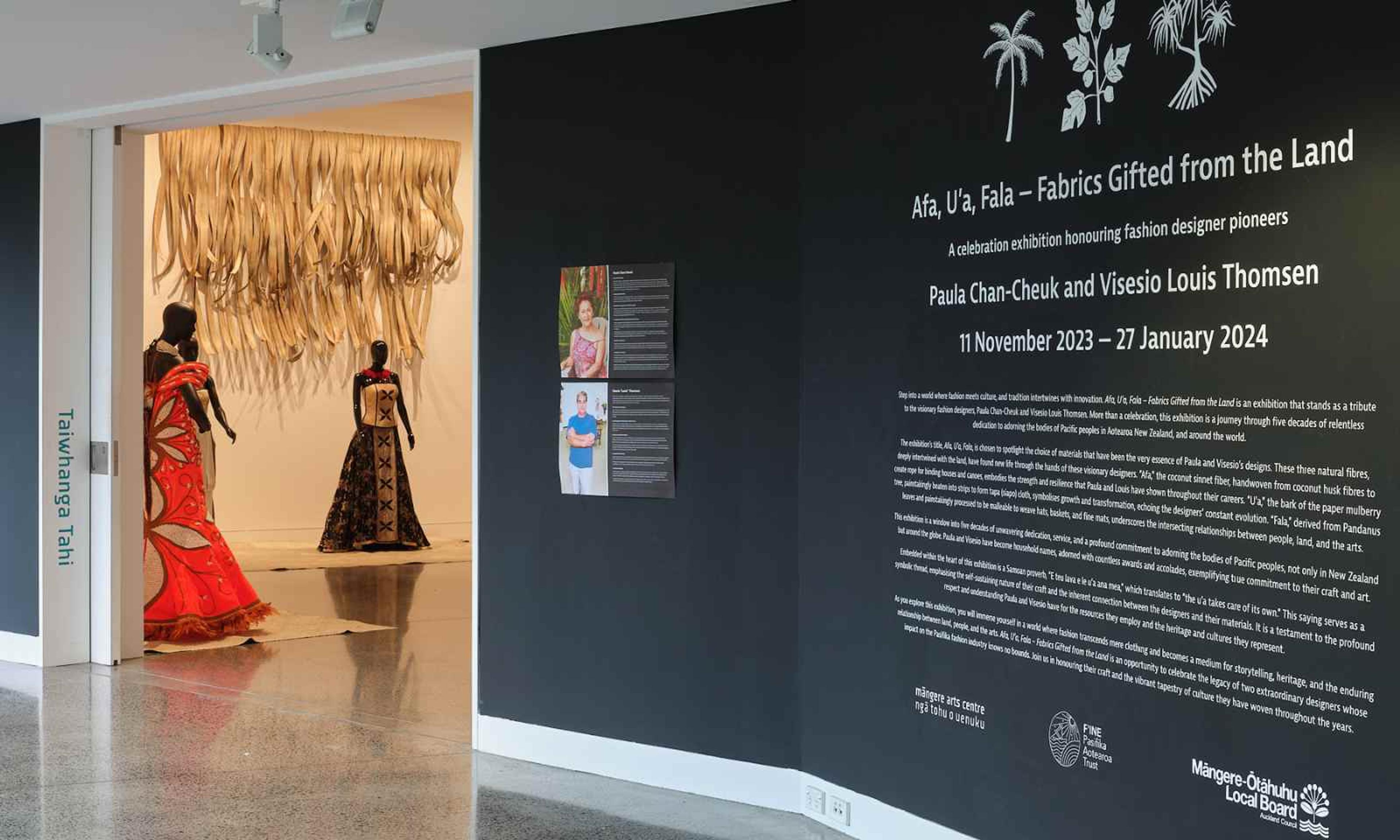

The Afa, U'a, Fala - Fabrics Gifted from the Land exhibit featuring work by Paula Chan-Cheuk and Visesio Louis Thomsen.

Photo/ Supplied/ Māngere Arts Centre

Exhibition is a tribute to hard work, resilience and Pacific fashion excellence

Māngere Arts Centre's latest exhibition celebrates one of Sāmoa's fashion designer pioneers - Paula Chan-Cheuk.

There was a time in the history of Auckland’s Sāmoan brides when your wedding simply wasn’t going to cut it if your dress wasn’t designed by Paula Chan.

This was when the prize for the puletasi or traditional wear section of the Miss Sāmoa pageant seemed to be reserved for her work alone.

She’s so good that she has garments displayed in three museums — the British Museum in London, Te Papa in Wellington, and the Auckland Museum.

The Afa, U'a, Fala - Fabrics Gifted from the Land exhibit featuring work by Paula Chan-Cheuk and Visesio Louis Thomsen. Photo/ Supplied/ Māngere Arts Centre

And to celebrate her decades of fashion excellence, the Māngere Arts Centre is paying tribute to her enduring legacy through the Afa, U'a, Fala - Fabrics Gifted from the Land exhibit which features work by both Paula and Visesio Louis Thomsen.

But where did it all begin for Paula?

Her father Cheuk Chan immigrated from Canton, China, to Sāmoa as an indentured labourer in the late 1930s. There he met and married Paula’s mother, Pepe Malia Matalena, from the village of Faleū, Manono.

After four years as an indentured labourer Chan and Pepe Malia ran the village shops of firstly Toamua, then Vailu’utai. Money was scarce and life was hard.

Paula was born in 1950, the eighth youngest of 16 siblings. Paula was effeminate, a trans girl, and bullied at school. The teachers made sure the bullying never got physical but it was painful nonetheless.

As Paula grew, like many trans people in Sāmoa, she was simply accepted by her aiga. It was only her father who had difficulty adjusting to his child’s sexuality.

“He used to get angry, but he couldn't do anything,” says Paula. “My mum was my main fan and she used to let me wear dresses. She used to fight with my dad because of me sometimes.”

If there’s been one constant in Paula’s life, it’s been her mother’s unfaltering support. It meant that Paula never once doubted who, and what, she really was. She was a lady. Simple and plain. A damn hard working lady, but a lady from head to tail.

When Paula was 11, the family moved to Taufusi, the first urban residential area in Sāmoa’s capital of Apia. Taufusi is Sāmoan for “swamp”, which gives you an idea of the conditions around their Pālagi-style fale.

Her parents worked hard. Chan specialised in menswear for the well-to-do of Apia society. He made iefaitaga (formal lavalava) and jackets for faife’au (pastors) in particular.

Pepe Malia helped out with the sewing while also supplementing their income with work as a cook for the prominent families around town.

It was the perfect training ground for young Paula, who watched and practised on her parents’ offcuts every chance she got. They taught their craft so well that Paula was soon earning her own money making dresses from her parents’ leftover fabrics at the age of 14. By the time she was 15, she was paying her own school fees at St Joseph's College, by selling her creations for four shillings each.

But after her father had a stroke in 1961, there was now pressure on Paula to help support her large family.

*

I met Paula in her cosy house in Māngere Bridge, in her lounge, looking out at her beautifully wild flower and vegetable gardens. At 71, she looks every bit the lady. Her manners are gentle and delicate almost. Her hands and fingertips move while she talks, but it’s not Latina gesticulating, loud and attention-calling. It’s more Oriental elegance. Or like a taupou dancing a taualuga, and accentuating her words with her hand movements.

Listening to her many stories, I get the sense of a woman with a steely determination.

Paula came to New Zealand in 1974, and she has probably worked every single day since then. Her parents and two younger sisters arrived at her three-bedroom Mt Roskill flat in the late 1970s. She started out as a machinist, sewing gloves in a factory but didn’t last more than six months. The work, she says, was too fiddly, so she rang a place in Karangahape Road and got her first job doing CMT work — that’s Cut Make and Trim — contracting for excess factory work.

But the flat seemed smaller and smaller. They needed more space. She calculated that she’d need three years to save enough money for a deposit on her own house — and that she’d need more than one job.

So, for the next three years, Paula barely had time to look up from her sewing machine.

It was up at 5.30am for the 8 o’clock start at her first job. She’d finish at 4.30pm, then take a bus to a factory in Morningside where she supervised a team of sewers until 9pm. Then another bus to get her home at 10.30pm for dinner. After which she’d be back to the sewing machine for her third job — sewing surplus items the local factory contracted out to “home” workers like her.

On top of that, she was doing private work for her own clients — making evening gowns, wedding dresses, christenings gowns.

In 1983, she started a three-year course at the New Zealand College of Fashion Design but did it in two years. All her experience with the factories and her natural sewing ability meant she was able to skip the practical year of study.

So much work, so much determination. And in 1986, all her hard work paid off. She bought a house in Māngere Bridge, where she lives still, for $72,000 (it’s now valued at just under $2 million).

It’s been a haven not just for Paula and her parents, but also a gathering place and stopover destination for many family members from Sāmoa — siblings, nieces, nephews.

Her father had a second stroke in 1989, leaving him bedridden and Paula gave up her work in Auckland city to be a carer for her father.

Mr Chan died in late 1990 and her mother Pepe Malia in 2016, at the ripe old age of 99 years and three months.

*

Paula’s dreams, however, did not stop at her house. With her new house, she gained new energy and, after a holiday in Australia, she returned with a new appetite for life and the perfect platform to spark her new life — the Miss Sāmoa beauty pageant.

In the 1990s, thanks to her growing fame in Auckland’s Sāmoan community, she found herself more and more in demand for any event requiring both high-fashion looks and Pacific style. This meant weddings and, not surprisingly, the Miss Sāmoa beauty pageant.

Her friend Lusia Reedy, owner of the famous PolyNZ nightclub, was sponsoring a competitor - Julie Toevai - and she asked Paula to design a dress for the traditional wear section.

“I thought about what traditional wear was for us Samoans and it was bark and leaves,” says Paula.

“People were saying it was the puletasi and some were using satin, but traditionally we didn’t have those fabrics.”

“So I thought I’m going to go back and use siapo.”

Toevai won the Miss Samoa New Zealand competition in 1991 and then also won Miss South Pacific in 1992 and Paula’s reputation was made.

She became the queen behind the actual Miss Sāmoa queens. Ten of her clients won the pageant wearing her designs. For years, it seemed like she had a monopoly on the Traditional Wear section.

Paula was the first to incorporate u’a (the white, unprinted siapo or tapa cloth) and lauie (the very fine, fine mat) into her dresses, but there was also the normal siapo, ie toga (fine mats), and island prints. Her fame spread across Auckland and in Sāmoa. Every competitor, every young bride, wanted a dress designed by Paula Chan.

It was a huge platform for her work but more importantly, it was a huge platform for the launching of Polynesian design and a revival of pride in Pasifika styles and fashion.

In the words of the Miss Samoa event coordinator Jeanie Hansell: “Paula provided the winning format. Her competitiveness was incredible. Everything had to be worn exactly to her specifications, even down to how the girls’ hair had to be arranged.”

“She reignited our use of traditional fabrics incorporated into after-five attire. It was such a fantastic platform for her — and she led the way for reviving our fashion using traditional resources, so pivotal to our culture.”

Paula says she’s made more than 200 wedding dresses, and countless other garments for competitions, christenings, 21sts and an extremely long etcetera — all the while building up a formidable reputation in the Pasifika fashion design world.

It’s no wonder her work is in three museums. Back in 1992, she was the first to incorporate organic material into her work — the ietoga or fine mats. Her use of siapo, afa (sinnet) and seashells have become synonymous with her work. Te Papa was the first to ask for one of her creations. The British Museum then saw the dress and commissioned one for themselves — and, soon after, the Auckland Museum did the same.

*

Not surprisingly, she’s also a role model for LGBTQ+ people. But while she’s comfortable in her own skin, and comfortable in her identity as a trans woman, she doesn’t see herself as a typical fa’afafine.

“I don't like the way the term fa’afafine lumps all gay men and everyone together.

“I prefer the term trans and I don’t like calling attention to myself.

“I'm very discreet. And I'm not going to live my life for them. I'm living my life for me. It's between me and God.”

She has no time either for the moralistic judgments of others.

“You know, we're all created out of love. If you understand the Bible, that's what the Bible says. Love thy neighbour as yourself. God created everybody out of his image of God. It's only God that can judge me.”

What advice would she give?

“I think it’s to be honest with yourself. It’s no use living a lie. That’s how I live. The things I’m most proud of in my life are living my life the way I wanted, and my family.”